George W Knapp

Name: George W Knapp

Rank: Captain

Date of Birth: July 14, 1916

Birthplace: New Lenox, IL

War: WWII

Dates of Service: 1943 – 1945

Branch: US Army

Unit: 4th Infantry Division, 12th Regiment

Locations: Europe

Prisoner of War: No

Awards: Purple Heart, Bronze Star

Interview Transcript

Today is March 10, 2008. This is Fidencio Marbella of the Melrose Park Public Library. Also present is Heidi Beazley of the Melrose Park Public Library [also present is Virginia Knapp, wife of Reverend Knapp]. Today we will be speaking with Reverend George Knapp. Reverend Knapp is a current resident of LaGrange Park, Illinois. He served in the United States Army from 1943 through 1945 and the highest rank he achieved was as a captain. This interview is being conducted for the Veterans History Project at the Library of Congress. Let’s go ahead and get started. Why don’t you tell me Reverend Knapp when and where you were born?

Well, I was born in New Lenox, Illinois which is about forty miles south of here and I was the first child of my father whose name was also George and his wife Katherine.

Do you have any siblings?

My brother Marvin was two and a half years younger but he passed away at the age of eighty, so he’s been gone quite some time.

What did your parents do for a living?

My father when I was born was working for the EJ & E Railroad, but he had been born and raised on a farm and he enjoyed farming so he became a renter and he rented a farm a few miles from New Lenox in Manhattan, Illinois and of course that is southeast of Joliet. So he farmed his entire life in that general area. He was always a renter. Never owned a farm but he rented two or three different farms before he retired. Then my parents moved to the little town of Manhattan.

So you were born July 14, 1916. Before you entered the service the world was already at war. Did you and your friends have any sense that the United States was going to be drawn into the war as well?

My brother was in the service before I was. He was younger and of course as a clergyman I was exempt from the draft.

So you were already in the clergy before . . . ?

Yes, I went out from college, I went to the seminary. I went to Joliet Junior College, two years, and I went to Elmhurst College for one year only because of the fact I had so many credits they said you don’t have to be here for two whole years. So anyhow, I graduated from the college and went to Eden Theological Seminary. The college and the seminary are both institutions of the United Church of Christ and I am a member of that denomination, United Church of Christ.

Where were you when you heard about Pearl Harbor?

I’ll tell you what, that was really something. We were serving a church in southern Illinois, Lensburg, and we had one son and on that particular Sunday after I had services in the morning, we went to see Virginia’s parents back in the St. Louis area and we really hadn’t heard anything on the car radio, which wasn’t working too good on that old car we had, but when we got back and went to the church that evening for a youth fellowship meeting the young people were telling us what had happened at Pearl Harbor. That’s how we learned about Pearl Harbor. While we were gone in St. Louis, in a suburb of St. Louis to visit my wife’s parents that day why this all happened. The young people, were just, that’s all they can think about. That’s how we learned that Pearl Harbor had occurred.

What was your reaction like when you first heard the news?

It was just very, very difficult to believe. I think the whole United States was shocked at what had taken place.

So you ended up joining the army in 1943, did you enlist or were you drafted?

Like I said, chaplains were exempt from the draft and we had one son and when they started drafting young fathers from my congregation, some of them had one child, or two children or more, I just felt I it was my duty then to volunteer as a chaplain. Of course a clergyman had to volunteer, whether you were a Catholic priest or a Jewish rabbi or a Protestant minister. You were all exempt from the draft so in order to become a chaplain, why, I had to volunteer, so I did.

Why did you pick the army over the other services?

Well, I just, in fact I picked the army because at that time there was no Air Force. There was an Air Corps. The Air Corps was part of the Army and I figured, well I had my fingers crossed. I always liked airplanes and I figured, well if I became an Army chaplain there was a chance I would be assigned to the Air Corps and of course we didn’t live too far from Scott Field Air Force Base at that particular time, so that is where I went to sign up, so to speak, and get my uniform and so on. So that in plain words, symbolically I had my fingers crossed hoping I would get assigned to the Air Corps part of the United States Army at that time. Of course at Scott Field Air Force Base that was the closest army base around which was a part of the army at that time, like I said. So I went to Scott Air Force Base and enlisted and did my preliminary paperwork and also bought my first uniform, which I’m still wearing! The thing is we only got $200.00 as an allotment for everything that we needed. That included clothing and military chaplain supplies. Like I brought here, my field altar, so that in order to get as much as I could for that $200.00, why then I bought everything used. I bought used shoes, my first army boots were used and this uniform was used when I bought it. It still fits and it’s very well made. So after all these years, even though it was used when I bought it, why it’s still in pretty good shape. Of course when we were in combat, naturally this uniform was still back in England and eventually when the fighting just about ended, they sent our footlockers from England over to us, wherever we were, in France or Germany. So then I got my uniform and of course in combat, naturally we were dressed just like the other soldiers. Combat fatigues and boots and everything else. The only thing that distinguished me from, was of course my chaplain’s cross and at first I had my 1st Lieutenant’s bars on and then I became a Captain. I was promoted while we were in combat, but I did with the army fatigues, the fighting uniform so to speak, why the only way they could tell me from other officers was that I had the cross on instead of the crossed rifles which the infantry officers had. And then I always wore a black chaplain’s stole which of course I have with me in my communion set here. When I had services I had my black chaplain’s stole over my army fatigues.

What was the reaction of your family, in particular your wife, when you decided to enlist in the army?

Well, I think they were sort of all shocked, although my younger brother was already in, so I suppose my father, my parents sort of took it for granted that it was a natural thing for me to do, but my father-in-law had been in World War I so we had quite a military background on my wife’s side. But my brother was already in. He was a sergeant. I guess it just became natural that they expected. The armed forces needed chaplains so somebody had to do it.

After you enlisted, where did you go for your training?

Harvard University was at that particular time, the chaplain’s school was at Harvard University, so I can always say I’m a Harvard man! But of course there were three or four hundred of us who were at the chaplain’s school at that particular time training because in 1943 things were really getting going and there were a lot of classmates there and some I bumped into overseas, some I never saw again. It was quite interesting to have the chaplain’s school at Harvard University at that particular time. On the first day before my birthday, I took the train from St. Louis and headed for Harvard University. So I missed my son’s first birthday.

What was the training like at Harvard? I imagine it was quite a bit different from a combat soldier.

We did naturally a lot of book work, but we had in the wooded area behind the university dormitories, that’s where we had our combat boots on and do a lot of marching, training, maneuvering, so that we were able to fit in with the rest of the fellows. We had a great big open field there on the athletic field, where we did a lot of the drill work. I’ll never forget this one tall fellow; he was a red-headed clergyman much taller than I was. He was at the beginning of the column as we were moving along and the drill sergeant gave the command, “To the rear, march!” He didn’t hear it or didn’t know what it meant so he just kept on going and then after a while the drill sergeant, young fellow, he said to all of us “Halt!” Then he called this fellow back and he was just way, way afar. That’s something you just never forget. We had a lot of drilling and training in whatever would be necessary to ready us for being out in the combat area.

What were the facilities like that you were in? Were they pretty primitive or did you stay in barracks?

We were, I think there were four fellows in this dormitory room.

So you stayed in dorms?

We just lived in the dormitory of Harvard University and had our classes in the big classrooms and of course the outside maneuvers were out on the athletic field.

What were some of the classes that you had to take?

You really got me there. We were given all kinds of military information but for the life of me I don’t remember the specific classes or books or the names of the courses. We had to learn how to read the military maps of course.

How to navigate?

Yes.

How long were you at Harvard?

I think just about five weeks.

So once that training was over, where did they send you?

Well, I was able to, Virginia will have to remind me of some of these things. Then from Harvard, oh I know now that I’m thinking about it, from Harvard University when the classes were all over with after five weeks the telegram, cablegram came from the Adjutant General’s department in Washington, D.C. and told us where each one of us was going. So I went down the alphabetical list, noticing where the other fellows in my class were going. George W. Knapp, 4th Infantry Division, Fort Dix, New Jersey. I had to get a train ticket and go to Fort Dix, New Jersey and when I got there I was assigned, like I said before, to the 12th Infantry Regiment of the 4th Division. A division is about 15,000 men and there were three regiments and so there were three chaplains with each regiment and when I went to the headquarters which was the chapel of our 12th Infantry Regiment there at Fort Dix the other two chaplains welcomed me. “Welcome aboard chaplain. We are a hot outfit! We’ve been packed up twice already to go to Africa but then they recalled the orders and we’re still here. But we’re a hot outfit, so welcome aboard.” One was a regimental chaplain who had been there for quite some time in the military for a number of years. He was the Catholic chaplain and then there were two Protestant chaplains. The other chaplain was a Lutheran and he hadn’t been there too long before I got there. But like they said, welcome aboard. As soon as I could I got to the telephone and of course I called Virginia back in the suburb of St. Louis and I told her what the situation was. Luckily my brother had had a new car before he went into the service and he could not have a car with him as a sergeant on the base where he was and so we were using his almost brand-new car. So Virginia and the one-year old son got in the car and her elderly aunt came along to just sort of give her some comfort on the way. The one thing that was interesting, you couldn’t buy maps in those days because nobody was, they didn’t want maps to get into the hands of the wrong people. So you didn’t have a map did you? [to Virginia]. So she just had to sort of follow the road signs with a regular, I don’t know if she had a geography book with you? But she just had to follow the road signs. So she got out there and of course we were at Fort Dix for a while and at that time we rented a house in a nearby town, not a house but a room on the second floor where I could stay with them at night. Sometimes she would drive me out if she needed the car during the day. Sometimes I would drive out and do my work at the chapel. A lot of times we would be out on field maneuvers or would be working at the chapel for the upcoming services, making hospital calls on the fellows that were sick in the hospital there at Fort Dix. We were there for a couple of months, wasn’t it Virginia? She and the one-year old son, they stayed in this little town outside of Fort Dix and I would spend the night with them. I used to stay out at the base where I had my quarters.

So this would have been late 1943, early 1944?

Yes, that was late in1943 because of the fact, like I said, I went in and had only five weeks of chaplain school so it was in the latter part of the month, of that year and then Fort Dix was transferred down to, what was the name of that camp? Camp Buckner? No, no, anyhow . . .

Virginia: Pensacola, Florida.

Down to the state of Florida and we stayed there of course, we all drove down there together and we didn’t know the east coast at all, driving from New Jersey down to Florida. The other Protestant chaplain was from Virginia and he knew that area quite well so we followed him and he was leading us the way. He had two boys and his wife in the car and the three of us in our car and we had to be sure we kept him in sight so that we could follow him and get to the right place at the right time.

Virginia: Are you aware that the national speed limit at the time was thirty-five miles an hour?

So how long did that take?

It took a long time, yeah. And we would have to stay at a motel or two on the way down because it took quite a while to get from New Jersey down to Florida. I know that this is sort of a silly thing to do but I had to urinate one time so badly because I had been drinking coffee and things like that but I didn’t dare leave him because I had to follow him. Finally we all stopped at the gas station. He had to stop at a gas station so then everything went alright from then on! When we got down to Florida we were at a camp there in Florida doing amphibious training. The camp was right near the ocean so we did our amphibious training and of course I was not a swimmer but I had to, we had to prove that we could swim to be able to qualify to go overseas and Virginia said “Why did you work so hard to prove that you could swim?”

Virginia: When he really wasn’t a swimmer!

So anyhow the water was pretty chilly there even though it was getting towards the end of fall and the beginning of winter time. The water was pretty chilly but we did, I just didn’t want to admit that I wasn’t a swimmer, but I swam enough that I qualified as a chaplain who would be involved in the invasion. So then we were given a little free time, November was it? Thanksgiving? Between November and, somewhere between Thanksgiving time we had a couple of weeks of leave after our training was through there so we drove back up from Jacksonville, Florida up to the general Chicago area, first stopping at St. Louis to see Virginia’s parents and family and friends and then kind of came up to the Chicago area where I had most of my family lived south of Chicago here, southeast of Joliet. So then we visited here and drove out to the east coast where we were going to be shipping overseas from New York, the Port of New York in January, that was in ’44 wasn’t it? 1944. So we had a little bit of time there together and I have written some of my things down but it was just, after we were through with our training there, for a short time there we were going to be taking off from another port to catch the ship to go overseas. I’ll never forget how I felt when I, I can still see in my mind’s eye as I was preparing to get on the train to go to the ship, why I looked back and there was Virginia and the one-year old son were walking away and as I remember, they never looked back.

Virginia: Didn’t dare!

Didn’t dare look back, but I watched them until they were out of sight and we got on the train and went to the port of departure. Shipped overseas there in January.

What was your trip overseas like? Going on the Atlantic in the middle of winter?

The trip was very good. It wasn’t abnormally rough or anything. And there was a ship’s chaplain of course. Naturally the ship had its own chaplain. We and the chaplain conducted services on the ship for our men on the way over and the Catholic chaplain would have his services. We two Protestant chaplains would work together or individually having the services for the Protestant men on the ship. I think if I remember right we had a service, some kind of a worship service every day, maybe sometimes just a devotional service, prayer time, and of course if it was, once or twice, especially if it was a Sunday we’d have a regular, formal worship service. If there were men in the hospital, in the ship’s hospital because of seasickness or illness or whatever it was, we would visit them so we were kept very busy. You’re always busy as a chaplain or a minister in a church because there’s always something going on that you could be doing.

How long a trip was this? How long did it take to get to Europe?

I think about ten days.

Had you ever been on a big ship like that before?

No, no, had we? We had never been on a ship. We were always traveling by automobile on our honeymoon and so on. This was quite an experience. But everything seemed to work all right and the food was good. They called me the “chowhound chaplain” which I still am, I guess, because I’m quite an eater. But we had a good trip and we landed in England and we were quartered in, or stationed in Budleigh Salterton in South Devon, not too far from the English Channel because then we were able to have our training exercises, our amphibious exercises on the English Channel. Not too terribly far from where our camp was.

What was the amphibious training like?

Well, we got into our amphibious landing craft, the kind of boats that we were actually going to be taking us over to the shores of France for the invasion. So we actually got trained in what we were actually going to have to be doing when the invasion took place.

When you were in England, did you have much contact with the British people?

Oh yes, yes, I’ve been reading some of the notes that I took and of course there was a nice church, a protestant church in this town of Budleigh Salterton. We were able to use the church for our services and we would have a, after such time the civilians were not using the church then we had our Sunday worshipping services and we could use it for bible study and other religious activities.

Do you have much of a chance to see other parts of England?

No, not too much because we could not get to London. We were about seventy miles from London and we had orders not to go even as a chaplain and I was only a lieutenant then, but even as an officer I was not allowed and I had my own jeep too. Every chaplain had a jeep and trailer so that, in fact I must go back a little bit and correct that statement. We did not have our own jeep while we were in England, but we could always order a jeep and driver from the motor pool. But as I said, we were not permitted to go to London. We just had to stay in Budleigh Salterton and the nearby area. We did go to, part of our outfit was in Exmouth, a few miles from Budleigh Salterton. Because of the fact that with two Protestant chaplains and three regiments, why we would have to take turns going from the regiment to which we were assigned to the other regiment where the Catholic chaplain was. And he would have to by jeep go to the other three regiments. I mean battalions of the regiment and have his Catholic services. The other Protestant chaplain and myself would take turns going to what we called the 2nd Battalion. The other Protestant chaplain was with the 1st Battalion and I was with the 3rd. So we would go to this 2nd Battalion and have the services there. Every once in a while we would have this Celebration of the Lord’s Supper, Holy Communion, and that’s why I have lots of memories of using my communion set out in the field and in civilian churches and so on. But of course as you know the rules and regulations were over there the same as here that at least we Protestant chaplains could not use a Catholic church and the Catholic chaplain could not use the Protestant churches so if there was no church of our particular religious affiliation in that town, then we had to have our services out in the field or along the beach. I remember a Palm Sunday service we were on the beach, it was chilly and it started raining, but that didn’t prevent us from continuing the service.

What was the mood like of the soldiers before the invasion?

Well, we’re a little bit, quite concerned. I remember General Eisenhower came over to speak to our group. They were on maneuvers out in the field and I never did get to see him at that particular time because he did not get to see every unit of the 12th Infantry Regiment at that time. So I did not see him at that time. Of course the soldiers, a lot of them had volunteered like I did. I presumed most of them had been drafted. They just knew this was something our country was involved in and it was something we were, that we had to do. We just followed orders. I know that Virginia and I talked about it, that we read about the fact that I had said in one of my notations or letters to her that we were on maneuvers in England and it was a little bit downhearted to realize that we found out we were going to be part of the invasion. I think in one instance there after we were in the invasion, why we had been fighting very intensely and I heard two of our young company commanders telling about the fact they had just gotten orders to move on farther into France in Normandy and keep on fighting and they were so heartsick in a way that their men were so exhausted, not having had any sleep and not much time to rest, to eat even, and those two young officers were very downtrodden and when I started listening to them and heard their stories and how downtrodden they were why, I did get very depressed myself and I went across the field and laid down alongside a fence there in the French area and had a good cry, I really did. I was just very, very downtrodden and broken-hearted about what I had just heard them telling about. Then I said to myself, hey, listen. You volunteered for this job. You’ve got to get up and do your job. So I did have a good cry over the whole thing though and finally I said well now I volunteered for this job and I’ve got to be a good chaplain so I sort of, in plain words, dried my eyes and got up and continued on and I don’t think I ever felt quite that bad after that but I sort of got it out of my system and tried to serve these two young officers and all the other officers and men the best way I could. But we were in constant combat as the 4th Infantry Division for eleven straight months and that meant we were in contact with the, well there was a period of 199 days we were in constant contact with the enemy and it was pretty rugged for our men. We had the highest rate of casualties of any outfit that fought in Europe. So the 4th Infantry Division, of course it was in WWI, we had all this time in WWII. They’ve served in Vietnam two or three times already. They go over for a year of duty, they come back and rebuild their forces and their strength, their morale so to speak then go back again. I think part of the 4th Division is in Iraq right now. But like I said, we had 400% casualty rate and people say that’s impossible, you were wiped out four times but of course as our men were killed and wounded, why the replacements kept coming across the channel from England where they were being trained to do that very thing and so our ranks were always being filled up as our men were killed and wounded and sent to the hospital, why then our ranks were filled up but we did have a 400% casualty rate. The highest casualty rate of any unit that fought in WWII, in the European theatre.

Virginia: I always wondered how he ever made it!

The odds are so much against you.

But I was wounded. That’s why I wear the Purple Heart, but anyhow, we did lose one chaplain. There were fifteen chaplains to every regiment, enough to serve, three chaplains with each battalion and there were three battalions and then we had the artillery unit and the tank battalion in that part of the regiment, so each unit had their own chaplain and so as I say, we only lost one chaplain that I remember with the enemy fire. He was in the regimental command post at that particular time and the enemy, that was in Normandy, France and one of the machine gun bullets came across the area and into the headquarters tent and hit him right in the heart. So that was, I don’t remember of any other of our fifteen chaplains who were actually killed but some of course became, in plain words, became, had combat exhaustion or became physically ill and they would have to go back and be placed into another outfit that wasn’t in combat or maybe be sent back to a hospital in the United States or in England and so I never did have to go to a hospital. My wounds were such that they were taken care of at the company aid station. But like I said, we did lose one chaplain from enemy fire. And it was at one time that we were always up there with the men where they were actually doing the fighting, so as soon as they were wounded we could take care of them but our division commander got word of that. He only had, there were fifteen chaplains in the entire division and so he realized that if he lost any of his chaplains that who knows how long that it would take before they would be replaced. So he gave the command out that we were supposed to stay, come back from the actual fighting combat area and be at the regimental aid station where the wounded men were coming. They were all being brought by litter bearers. That’s where we could take care of them. He didn’t want to lose all of his chaplains right away. So as I said, there’s only one that got killed, but we were then at the regimental aid station where the wounded were brought and many of them died there after they got to the aid station. So we would be taking care of them as they were breathing their last and sometimes it doesn’t seem that it was very significant, but I was not a smoker and still am not but a lot of these fellows, their hands were wounded or they were unable to light a cigarette so we would take a pack of cigarettes, light it for them, put it in their mouth, let them take a few drags and then take it out for a while, shake the ashes off and it gave them some comfort. Sometimes they only, the other thing we did was give them a drink of water because that was all we had. There was nothing there up at the front. Give them a drink of water, let them have a few drags on a cigarette. So whichever way we could do, we would visit with them, talk with them if they were able to talk and share our experiences with them and a lot of times they liked to talk about their family back home. Of course a lot of times we gave them the last rights because this was the end of their life. And they were always able to have a little private communion set here if I knew them personally and if they felt they’d like to have a private communion right at that time before they were taken back from there to the field hospital and then eventually to a hospital in England or back to the United States eventually. A lot of them did feel like they’d like to have the Lord’s Supper, the Holy Communion and if they were Catholic and our Catholic chaplain wasn’t around we served them the best way we could as Protestant chaplains.

What was the actual invasion like? You went ashore on what day? Were you there on June 6?

Yes, we were on this great, big passenger ship, I mean a troopship of course, and it was really, really packed and of course the men were not in too good spirits. They were downtrodden and their spirits were rather low because they knew what was going to be happening, but the ship was overloaded, not dangerously, but you would sleep wherever you could lie down. The food was always good and as I said before I was a chowhound. Anyhow, we were on the English Channel for a day or two longer than they expected because as you know the weather was terrible and Eisenhower and his weathermen and his fellow officers had to keep on deciding, well can we go or can’t we go at all. If they had waited another whole month until the moon was just right and everything else was right, why by that time who knows, the enemy would have found out what was going to be going on. As far as we were concerned at that particular time the Nazis were not aware of the fact that we had, that the invasion was being planned so soon, so we were on this ship a day or two longer than we were supposed to be and I don’t think, I think we just about ran out of food but a lot of the fellows really did get very seasick. I was lucky, I got a little bit woozy at times but I never got really seasick and so when the time came for the invasion, the invasion was really called for, Eisenhower and his fellow officers, June the Sixth, why the ship got as close as we were able to, to the shore and then we went down to the ship on these rope ladders and Virginia always wonders how I made it. I had to carry my equipment here and mess kit and other things like that. We had to go down the side of the ship, the rope ladders and get down into the landing craft, which were bouncing around down there because it was a little rough and so as soon as we got into the landing craft and it was filled with about twenty-four men, why then we headed for the shore and we were very, very lucky, there’s no doubt about that. A lot of the, as you know from history, a lot of those landing craft hit some impediment out there before they got to the shore. Sometimes the landing craft got stuck out there and the men just had to jump out into the deep water way over their heads with their rifles and their backpacks and everything, go under, completely sink underwater, come up and had to swim as best they could. Some of them never made it of course. But our particular landing craft, we were very fortunate, we went right up to the beach and when the ramp went down I walked out onto dry land. I mean wet sand, but we were, on the sand it was not, we didn’t get out into the water. So then of course we had to follow the direction of the sergeants and head eastward from that particular point and our first objective was the town of St. Mere Eglise. We had to follow that and of course this was six or seven o’clock in the morning. It was daylight, but from midnight on, before that, for hours before the paratroopers had been dropped in and also the gliders had been sent in. They were released from the ships that were pulling them. I’ll never forget, Virginia’s heard this story a million times I guess, but as we were leaving the beach and heading east on our way to get to St. Mere Eglise to free that city, why these great big fir trees and other kinds of trees were near the beach. They were, every once in a while you’d see a soldier who had been parachuted down and he landed in the tree and his parachute got caught in the tree and of course the enemy was on the ground so they shot him to death. But there they were hanging. Nothing we could do for them and a little bit farther on we saw the, some of these helicopters [gliders] which had been dropped in and they had been, this one I’ll never forget, it landed in this one great big tree and behind it, it was like a small airplane of course, behind these four men in the front there was a jeep that was tied down because they were going to be landing, get the jeep out and keep on going. But when they hit this tree, why the jeep broke loose from its moorings and crushed them not only against the glass in the front of the plane, but against this big tree and they were all killed. So there they were just sitting there as if they were sleeping. The impact killed them and they weren’t really terribly, terribly bruised or damaged. After prayers, we went by and blessed them and kept on going because there was nothing we could do for them at that particular time. We kept on going and eventually we did get to St. Mere Eglise and that’s the city where you remember this one paratrooper landed on the, his parachute got caught on this steeple of that church in St. Mere Eglise. So from there on after we had captured that city, we had to turn north and go to Cherbourg. That was our major objective; to get up to the north end of the Normandy peninsula and that was the 12th Infantry Regiment. We were given very specific directions and serious objectives. Our objective was to capture Cherbourg, the port city of Cherbourg. Of course when we got there it was under control of quite a number of German Nazi soldiers and their officers and of course when we took the city, we captured them. I’ll never forget this; the chaplain of these men was captured too. Of course he was a prisoner, one of our prisoners and so naturally I went to visit him as a chaplain and when we both realized we were chaplains, I know enough German that I could speak with him and he gave me a little Testament, in German of course. And I have it right here in my communion set and he signed it with his name and address. I never did get back to see him in his home town. That would have been quite an effort after the war was all over. Anyhow, he was a prisoner of the American forces and I suppose with his men he came back to the United States and was in a prisoner-of-war camp with his men.

When we landed on Utah Beach, the landing was pretty good. I’m glad Virginia reminded me of that because we were a couple of miles from where we were really supposed to be, but the navy didn’t drop us off exactly where we were supposed to be landed. Maybe that was a good thing because we were safe and as I said our landing craft landed and I didn’t even get my feet wet when I got on the beach there. One of the ones that landed with us was General Teddy Roosevelt , Jr. and Eisenhower, he of course was with our outfit and he told our commanding officer who was a two-star general that he wanted to land with us, with the landing troops and he was with our 12th Infantry Regiment. Not too far from where I actually landed. Anyhow, they said we don’t want you to land there. We don’t lose a one-star general in the invading forces like that. So he said you can court-martial me if you want to, but I’m going to be there. So he was and he was using a cane! No wonder they didn’t want him to land there in his condition, but he was there so he followed us to St. Mere Eglise. Then on the way to Cherbourg he had a heart attack and he didn’t die because of a combat wound but he died because of his heart attack. Whether that was all partly due to being there, but at least he got his wish and he was part of the invading troops. I did not have part of his memorial service but I attended his memorial service there near Cherbourg, right out there and I was privileged to be a part of his memorial service there on the front lines.

After the 4th Infantry captured Cherbourg, what happened after that?

Well then, after we captured Cherbourg, why then our next orders were to go down to St. Lo. You’ve heard about the St. Lo breakthrough, and of course it was quite a distance from Cherbourg to, maybe forty miles, but it seemed like a long ways at the time. Could’ve been seventy miles, but there was a lot of fighting there, but it wasn’t as bad as it had been before we got there. Other forces had freed the city from the Nazis and so when we got the order that we were supposed to leave St. Lo and travel day and night to the city of Paris why then of course that’s what we had to do. The St. Lo breakthrough was really something that I can still feel, really. There were at least a thousand or two thousand airplanes came over from England and other parts of France flying over our heads. Most of them were leaving England, of course. There were fighters and bombers and they were flying over our heads at St. Lo as we were marching east and of course I always had a jeep and my driver was driving the jeep. We had a trailer behind us with all my religious equipment. When we were going without a whole lot of fighting from St. Lo to Paris we spent a lot of time in the jeep day and night to get there with very little to eat and very little sleeping. The reason we were going into Paris was because initially Eisenhower didn’t think that we should worry about Paris because he said it has no military value, at that particular time. There were a lot of Nazis there. Anyhow, his associates finally persuaded him that we should go into Paris and be a part of the freeing of Paris from the Nazis. It was going to be historic. The public would appreciate that fact, the rest of the Allied world. The Americans were part of the freeing of Paris. The British had come in already, but Eisenhower was persuaded that we should come in too and take part in the freeing of Paris. The Free French were coming in also because they were being a part of it. The French general naturally wanted to be a part of the freeing of Paris. So they came in from the east and the south and we came in from the west and we actually came in from the west and went along the south edge of the city and when we came into the city itself from the countryside I can just, of course we had all seen pictures of Notre Dame Cathedral and there was this beautiful cathedral. From there on we had to go down the Champs de Elysse to the Arc de Triomphe and meet with other military forces, the British and the Free French. It was quite an experience because the civilians had come out by the hundreds of thousands and were lined up on the Champs de Elysse to greet us as we were going. Of course I had my jeep and trailer and at that time it was the practice that chaplains would be given cartons of cigarettes by the Red Cross and we would give them out little by little to the soldiers and this was how the American soldiers got their cigarettes. They were provided by the Army to the chaplains to the soldiers. As we were going along the Champs de Elysse I decided, well I’m going to treat these civilians through some good old American cigarettes because people were just hungry for American cigarettes. They were worth more than gold actually. I started passing them out one at a time and most of the people along the streets there were women. A lot of young women and boy, did they go for those cigarettes and I made the mistake of reaching down and getting a whole pack of cigarettes and started to pass them out and boy, they just dove at that pack of cigarettes like chickens after chicken feed and they really tore the cigarettes all to pieces. From then on I was very careful how I passed out those cigarettes. So eventually we got to the Arc de Triomphe and went around it and came back that night I spent the night in a hotel in Paris with some other officers. So we were billeted that night in a hotel in Paris and like I said at that time we were not too far from the Notre Dame Cathedral and I thought, well it’d be really historic to have worship services in the cathedral, but I was informed that I could not do that as a Protestant chaplain. I could not go into the Catholic church, Catholic cathedral and the Catholic chaplain could not go into a Protestant church. That was just the policy at that time. So I had my services out in the open area somewhere. I did attend a service in Notre Dame Cathedral, which was held by our Catholic chaplain. It’s interesting. His name was Chaplain Freeze, wasn’t it? The other Protestant chaplain’s name was Kuhn. So there was Knapp and Freeze and Kuhn. A lot of short names. So I did attend a service there. It was a Catholic service for our Catholic men of our 4th Infantry Division. We didn’t stay in Paris very long but of course I did have, after my first night in Paris, being that I was not able to have services in the Notre Dame cathedral I guess I said I’d do the next best thing. We had already been through the Arc de Triomphe on the west end of the city so I got with my assistant who had my jeep so we took another sergeant and we drove to the Eiffel Tower and of course when the Nazis left the Eiffel Tower they knocked out the electrical motors. There was no electricity in the Eiffel Tower and it was about a thousand or four thousand steps we had to climb up to the Eiffel Tower. I might have been the first American to get up there because I had the free time do it and as an officer, why, I was sort of on my own. So my assistant and I and a few others walked up to the top of the Eiffel Tower and it took a whole hour because we had to walk up step by step by step and there’s over a thousand steps. When we were up there looking at that beautiful city I realized there was some fighting still going on in the streets of Paris and the bullets were flying around my head up there. Boy, if Virginia gets word that I was killed on the top of the Eiffel Tower, she won’t appreciate that at all! Luckily I was not hit. Later on we did have the privilege, years later, she and I went to France and we traveled around Europe, but anyhow, that time we took the elevator. It’s quite a beautiful sight. The bullets were really flying around our heads. There was still some fighting on the streets below and they would shoot at each other from the streets to a hotel window or something and miss the hotel and the bullets would keep on coming up to where we were.

So after you were in Paris, where did you head off to after that?

Like I was about to say before continuing on, we didn’t spend much time in Paris but naturally after the city was freed, our job as a fighting infantry unit was to keep on going and we headed out east from Paris and across Belgium. We got to the Huertgen Forest. You know how terrible that was. Our unit was involved in the Huertgen Forest for days and days and of course there were tall fir trees and other kinds of trees and the enemy was firing their artillery and it would hit into these trees and the shrapnel would be flying down all around us. Like I’ve often said, it was in the fall, September and October heading into November. Terrible fall weather, raining and thundering and lightning and I’ve often said the living conditions were so bad that human beings shouldn’t have to put up with that alone, without the fact that there was a war going on at the same time. I remember when we left that area our Service Company had to go out and pick up the blankets that had been used by these guys, like us, that had been in the foxholes. I know they picked up twenty blankets at the bottom of one foxhole because as the blankets kept getting wet, they kept asking for more blankets and they tried to keep as dry and warm as possible. The one thing that in the Huertgen Forest, the fighting conditions and the weather conditions were so terrible, why we were living on K-rations and that got pretty tiresome. Of course as I said before, I’m a chow hound and I did my best in eating every bit I could of the K-rations. One time there was a light lull in the fighting and I looked over and there was our kitchen truck. Our regimental kitchen truck had been able to come up with hot food and they spread their big pans of food on the little bit of open area in this forested area and it was very enjoyable to have good, warm GI chow. The dessert that time was peach halves, canned peaches. Oh I just loved that. Still do! So I thought, I’m going to have some more of those. There was a GI behind each food container and so when I put my mess kit down to this big container of peaches, the soldier behind it said “Sorry Chaplain, no more seconds!” I felt sort of bad but I was going through for the third time! Nobody had seen me or realized but maybe this was a different guy behind it. Anyhow, I didn’t say anything. I just realized that I’d already had my seconds and I didn’t get thirds! It was such wonderful food after we’d been eating K-rations in the Huertgen Forest under those terrible weather conditions. From then on after we were . . . Oh yes, if I don’t have things written down Virginia has to remind me. Like I said, when I went overseas our little son was a year old and when I left to go overseas, to really go back over to England across the ocean, Virginia was expecting our second child and so I was just wondering, will it be a boy or a girl? I just read that letter this morning that I was writing to her. I said I have a feeling it’s going to be a girl because we have one boy. When the second child was born, it was on the Sixteenth of July, wasn’t it? We have five kids, by the way, and they were all born, including my own birthday, in sixteen days in July. We have six birthdays, all five children. Some of them only two days apart. I don’t know how she did that! Anyhow, that’s true. I was wondering about when our second one was going to be born. Somewhere there in the, just before Huertgen Forest, it was in the foxholes in France. One day, two weeks after she was born it was the twenty-eight or the twenty-ninth of July, I got three communications: Virginia’s letter telling that the little girl had been born, the telegram that she had also sent, and the cablegram that came from the Red Cross that she had told them to inform me. All three came to the foxhole on the same day. So I really found out that I was a father again.

Was it a boy or a girl?

Joanie!

Virginia: She was just here. She lives in Olympia, Washington and went back yesterday. I hate to see her go back!

So my wife, we don’t mind being aged. I’m ninety-one. She’s eighty-eight, but she says she realizes that our oldest child is sixty-five. Old enough to retire and be on Social Security, oh my, makes us feel a little old in that respect. I did hear about Joanie’s birth after it occurred. About that same time our fellow chaplains recommended, they thought I’d been doing a pretty good job so they recommended me to be given the captain’s bars. Not too far apart I found out about my second child’s birth and I became a captain. I never got to be a major.

When you were promoted, was there any kind of a ceremony?

No, just the two chaplains out in the field in combat conditions, just had gotten word from headquarters that I had gotten this promotion. The one chaplain who had been in the service for quite some time before we arrived, he had been in that outfit during peacetime, so he had an extra set of captain’s bars, so they pinned the captain’s bars on me. Just the two of them. We had our own little private ceremony. Naturally I wrote back to Virginia about that. I told her about the fact that my income would go up and our housing allowance would go up and our food allowance would go up too.

After the Huertgen Forest, where did you end up?

We were so beat up, terribly beat up that our higher-up officers sent us to Luxembourg because there was not much fighting going on in Luxembourg. Isn’t that right ‘Ginia? Luxembourg. We had always been in the First Army. Well, we were there from the end of November, the first part of December and it was just like heaven after living in a foxhole in the Huertgen Forest for weeks like that. Here we were in a nice warm house in Luxembourg with electricity, most of the time. It kept going on and off. Luxembourg hadn’t been beat up, up until that time yet. We almost felt like we were at home because the houses looked like American houses and some of the people spoke English. A lot of the automobiles on the streets of Luxembourg City were American automobiles. Everything was fine until on one nice day, and this happened to be the Sixteenth of December, the Battle of the Bulge started. Across the Elbe River, which was Germany of course, the Nazis started firing on this city of Luxembourg. It was early in the morning and I was out there in the area in the village courtyard because our men were billeted all around there in all of the houses. The first shell came in and went into the window of the second floor of a house where three of our GIs had just been getting dressed to go out. They had left. If they had been there I’m sure they would have been killed. The second or third shell that came in to this courtyard, the village square, I was talking to our first sergeant of the battalion and it struck him rather seriously in the leg. A big piece of shrapnel hit him in the leg and it was bleeding quite profusely through his uniform so I took off my belt and made a tourniquet as best as I could above the wound to keep the blood from coming out. He was just a slender, young fellow, Huey Young. He had bright red hair and he was taken away as soon as possible by the medics on the stretcher and then the ambulance to a field hospital not too far away, then eventually to England and back to the United States. I just have to tell you that I did not see him then for twenty years because I never had a chance to visit him after he was released from the service. I came back home after the war was over and very shortly after the war was over, I became the national chaplain of the 4th Division Association. The National Association that included men from WWI and WWII. Most of the men that came at first were WWI men. They had a national association meeting every year. We met from California to New York, Florida, Texas, all over. So Virginia and I would attend almost every one of them and eventually I was elected as the National Association Chaplain. At every association meeting I had the prayers at the opening of all the meetings and had special services in a local church, if possible. It was twenty years before Sergeant Huey Young came to his first association meeting. Somebody told me that he was there and when I saw him, they told me this is Huey Young coming. I just couldn’t believe it! But he already had his nametag on. He had registered before we got there, and it said “Huey Young.” Like I said, he was slender, he was red-headed. Now he was very, almost overweight. He was a very heavy fellow and the little hair he had left was white instead of red and like they say, figuratively speaking I kept pinching myself, that this was really that red-headed sergeant that I had helped when he was wounded on the sixteenth of December in Luxembourg. I put a belt tourniquet around his leg. He was so glad to see Virginia and I because he knew her too and so we had to go up to his room and have a drink of wine with him. We saw him at a number of reunions. Haven’t seen him in a while, have we? Oh, he’s no longer living, but anyhow, what a change to see that this heavy-set, white-headed fellow was that red-headed sergeant that I had helped. Anyhow, you had asked too after the Huertgen Forest. That was a story of Luxembourg and of course when the Battle of the Bulge started by then Patton had been to the south of us with the Third Army and Eisenhower felt we needed somebody who was very much experienced in that kind of combat that we were going to be entering into as we went across Germany. Patton came up and took us over. He took over. The Third Army became the army that was heading across Germany to end the war, so to speak. It did end in about eleven months after it started. I think D-Day was on the Sixth of June and V-E Day was the Sixth of May in 1945. We had a lot of fighting and we were the first American troops to be in contact with the enemy as they were retreating back into Germany. I was so glad when we got word that the war was over. Virginia reminded me that I should be sure to mention what took place on V-E Day. We had been stationed, a couple of other chaplains and myself with our battalion and part of the regiment in Nuremburg, Germany. Because we were expecting, things were sort of winding down, so we got the word on the evening of May the sixth that actually the Germans had surrendered and combat was over, that we would not have to be involved in combat anymore. So we had been living in blackout conditions for so long, so that night the other chaplain and myself and our assistants, we went out and first we pulled up all the shades in our house, which was one of Hermann Goering’s castles in his hometown of Nuremburg. So we were stationed there in that castle. It was very, very nice of course. We went out that night and turned on the lights on our jeep and flashed the flashlights up in the sky and we did all kinds of things that we hadn’t been able to do for a couple of years. After combat was finished, we were an army of occupation for a while. Eventually they felt they had better things for the 4th Infantry to do and we got orders to go back to France, across France and eventually leave Le Havre and go back to the United States to train for the invasion of Japan because the 4th Division was always a hot outfit as they called it. The last service that we two Protestant chaplains had in France was in a great, big pasture, a great big open field. The men knew it was our last service there because we were going to be heading to come back home. We had four hundred men at that service, sitting out in that open area. They put their, they’ll be sitting on their steel helmet on the round part and they’d get a little bit tired sitting that way, then they’d sit upside down in their steel helmet and then they’d just sit on the ground. The other chaplain and I announced that this was going to be a communion service, the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, our last service in Europe, in France before we went home. We were going to have a significant service of Holy Communion. I said to the other chaplain, when we realized four hundred men were out there. We just roughly counted them. I said we’re going to run out of wine, although we did get wine from the local people as we were in France. Naturally the government wasn’t able to provide us with, they didn’t, we got it locally from the civilians. But I said we’re not going to have enough wine. He said don’t worry chaplain, as a Presbyterian we will use the Presbyterian in tincture method. So we had the men come up to each one of us, one by one. We took the wafer and dipped it in the wine and put it in their open mouths, put it on their tongue, so we had plenty of wine that way. I was sure glad he had an answer to my question. How are we going to have enough wine for these hundreds of men? Of course after that service, every chaplain had his own jeep and trailer and the other men were on trucks and we then went across France to Le Havre and got on a boat which was waiting for us to take us back home to the United States. It was the USS George Washington, wasn’t it? Virginia’s quite a musician, but I’m not. Those fellows had been doing a lot of traveling on the Pacific Ocean. For this particular time, to bring us home they came through the Panama Canal to go across the Atlantic Ocean and bring us home. Somewhere along the line they had picked up some new records, musical records to play. One they really liked, on one side was “One Meatball” and on the other side was “Sentimental Journey.” We heard both of them. I think we heard “Sentimental Journey” more than “One Meatball.” That really fit in to have “Sentimental Journey” because these fellows, the crew on that ship played that again and again and again, the ten days that it took us to get across.

Virginia: I think that they would be interested in your story. A chaplain with no gun and in Germany the German soldiers were just waiting for the American soldiers to come and capture them.

Just before they, well the war was ending and the Germans knew that, a lot of them were retreating east of course and we got to a little German town and a lot of the German soldiers had been surrendering to us. They were just waiting and in this one little town, right now I can’t think of the name of it, the German soldiers were all there, their rifles were stacked up in the courtyard of the village and they were waiting to be taken prisoner. They had seen and heard that we were taking pretty good care of them, of our prisoners, and they would be sent back to prisoner-of-war camps and maybe back even to the United States. Well, as I was there naturally just in my chaplain’s uniform, this one civilian came up and he heard me speaking some German. He was speaking to me and he wanted me to come with him and he told me he was a soldier even though he was dressed in civilian clothes. He had gone AWOL from his German army and he had been staying in with a civilian in a home in this small German village. I’m not going to go with him all by myself. I don’t have a weapon to protect myself so I took a big sergeant with me. Will you go with me and see what this fellow really intends to do? So we went to this civilian house in this little German village and he took us up to the second floor and there under the bed was his uniform and his rifle and his canteen and all of his other military equipment. So he had gone AWOL and these civilians had taken him in and given him civilian clothes to wear so he would be considered as a civilian in the town. But he figured he’d better surrender and go with the rest of his fellow soldiers and see what would happen. I still have his camera and the gun and of course another gun I have, never fired it, but it’s a real souvenir and so I got his gun and his camera. I still have the camera.

Virginia: We had the film developed and we thought we’d be able to tell something about his family and see if we could find them after the war was over. There were just fields he took pictures of. What they were, we had no idea. We couldn’t find anything. We were hoping to find him sometime but we never could. When they saw you they just surrendered.

You had mentioned attending the service at Notre Dame Cathedral. What was that like?

It’s tremendous, since then Virginia and I had been there. It’s very, very beautiful, tremendous and humongous is the word best to describe it. It’s very tall, very long and long as you come in and look down the central aisle all the way to the nave and to where the altar is. A tremendous nave, I presume they could have dozens of people in their choir. But I never did attend a civilian service there. Just attended this one that was conducted by our Catholic chaplain with his Catholic men. We were welcome to attend but as I said before I couldn’t have a service of my own.

Can you tell us a little bit about the circumstances around your getting the Purple Heart?

Well, I was wounded in the leg. Fortunately I didn’t need to be hospitalized but it was enemy shrapnel. Later on in Luxembourg that enemy shrapnel very seriously injured that sergeant and his leg was bleeding badly. I just put my belt on him as a tourniquet but my wound wasn’t serious. It had to be bandaged but whether you lose a leg or just get a small wound, you get a Purple Heart. I must admit, and I’m glad it wasn’t a very serious wound; it could have been bad enough like that sergeant. Like that other chaplain, just one bullet in his heart and he was gone. I was fortunate. Nothing you could do but just try to take care of yourself.

Can you tell us about your Bronze Star? How did you get that?

You had to be recommended by fellow officers and they gave me that because of the fact at first I was right up there with the men doing the fighting and being wounded. They just felt that that was a brave enough and courageous enough endeavor that I had earned the Bronze Star. Like I said, it’s not quite as high an award as a Silver Star but next to it, in recognition of what you’ve done under combat, to exhibit some bravery and help others.

You mentioned your unit was sent back to the US to prepare for invading Japan.

Yes, we were, after we got back from our training in Florida for this amphibious invasion we had some time, time to come back at Thanksgiving and visit friends and relatives in the St. Louis and Chicago area. We then, after a month of recuperation leave, why Virginia and I and the two children were driving in my brother’s car to the east coast where we were going to be having our amphibious training. On the way we heard over the radio, luckily we had a radio that got some pretty good news at that time; it was good news for us. We heard that the atomic bomb had been dropped, which was bad that we had to use such an instrument, but it was a quick way to end the war. So then we realized that the war was over and probably we wouldn’t have to go to Japan, but we did have to go to our camp and sign in and we got a little place to live. Because of the fact that the war was over and we were going to be continuing as a nation occupying Europe for who knew for how long, they told me, the Chief of Chaplains Office told me after we had been there awhile on the east coast I either had to get out of the chaplaincy right away or stay in with the possibility of going to Germany with the army of occupation. My own unit was not going to be going over as they had initially been scheduled to go to Japan. Since we didn’t have to go there we were, how would you call it, the unit was disbanded and everyone was sent to other units or back home if they had put in enough time. The war was over and they would be sent home, but as a chaplain I had one of two things to do, get out immediately, become a civilian or if I wanted to stay in I could continue being a captain but I would be over for who knew how long with a strange outfit in the army of occupation. I felt I certainly didn’t want to do that because I probably wouldn’t be able to take Virginia and the children with me. Anyhow, I decided to be relieved of my active duty and we came home. Virginia had been living in a rented house in a suburb on the west side of St. Louis and so, naturally coming back as a civilian, the thing to do was to become a pastor again. That’s at least what I decided to do. I probably could have become a chaplain in a hospital, something like that. If I had stayed in the chaplaincy, they said I would have gone over to Europe with the army of occupation. Then we came home and we were living in the same area where her parents lived and it was not too far from my seminary in Webster Grove, Missouri. That’s how I got to know her and meet her because I was doing my fieldwork as a seminary student in her church, in the same community where the seminary was. I let the authorities know that I was back and that I was willing to go back into the civilian pastorate. A church opened up in South St. Louis and in plain words we checked it out and I had a trial sermon and was accepted. I was actually in the service until the end of December. I was not on active duty, but I was considered on inactive duty, but still in the service so for the first few services if I remember correctly I think I wore my uniform in the first few services in December at that church in South St. Louis, that was Nazareth Church. After being accepted and installed, why we stayed there for three years. I guess for some silly reason, I decided I wanted to come back to the general Chicago area where I had gone to college and grown up.

Virginia: His parents were still here.

My parents were both still living and my brother at that time was out of the service and all of my other relatives were still; I came from a big family, especially on my mother’s side. We had many, many cousins so after serving the church for a couple of years in St. Louis, I wanted to come back up here and, Virginia didn’t say no, so we came back up and we served a church, after three years in St. Louis, we were four years in Blue Island, that south suburb and then I decided I wanted to make use of my GI Bill, which would give me educational privileges. My mileage was covered and my tuition was covered so I went to the theological school at the University of Chicago. I was going to work for my PhD. I was till doing that and driving about forty miles three times a week from Dyer, Indiana up to the University of Chicago. When we came back home we had the two children and then we had two more and then after our fifth child was born in Dyer, Indiana, I said the heck with the PhD degree! I’m just going to quit that and be a father and a pastor. That’s what I’ve tried to be since that time when I quit working on my PhD. We stayed out there in Dyer, Indiana and moved up to Peace Church in Bellwood [Illinois], a western suburb here in 1965 and stayed there for sixteen years and retired in 1981. I never really did retire because, until rather recently. When they found out I had retired in 1981, why the chaplain at Plymouth Place Retirement Home in LaGrange Park [Illinois] had just had a heart attack and died completely unexpectedly and so when the authorities at the retirement home found out I had retired, they called me in and asked me if I would be their chaplain. So I was there for nineteen years until 1981. I’m still serving the church, I’m still active. I’m serving a church in Melrose Park, right next door. So I’ve been there for quite some time. I don’t know exactly how long, I’ve been there for quite some time.

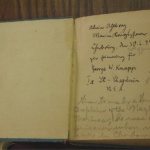

Can you take a few minutes and describe your communion kit to us?

This is me in my combat uniform.

Virginia: That was taken in Paris.

Like I said I had the cross on my helmet and the cross there and the captain’s bars on my shoulders. This is the chaplain’s stole. Like I said, I had to buy the uniform but the chaplain’s stole was provided. This uniform was packed up in the field locker except when the war was over with . . .

Virginia: It’s interesting that some of the funeral homes in the area that know him, if they have someone who’s a veteran and who doesn’t have a pastor, they’ll call and he still has the funeral service.

This was the chaplain’s flag that flew from the front fender of our jeep. So every military medical officer had a red and white flag, but every chaplain, and you can see this one was pretty well-worn, but it would be flying from the right front fender of our jeep. Wherever we went they knew that the chaplain was coming. Of course if the weather conditions were too terrible, we just wouldn’t have it out there. When we’d just be going slowly, from one area to another we always had our chaplain’s flag flying. This was the hymn book that was provided by the government for us and we had a pretty good sized case about four times as big as this for carrying all of our hymn books. I think we had about a hundred of them. This was a hymn book, no the New Testament that was given to me by this man whose wife had given it to him in December 17, 1943. He wanted me to have, but see this was bullet-proof, so you wore it over your heart in the pocket over your heart so that it would protect you. I was telling you about the fact that this German chaplain was a prisoner in Cherbourg and he gave me this little German hymn book. He wrote the date, it was the thirtieth day of June, 1944. I was a first lieutenant at that time but he was a chaplain of the Nazi marines and like I said he was a prisoner and we captured him in Cherbourg. Like I said, see page eighteen, but that is in German, “A mighty fortress is our God.” Of course I know enough German that I can understand that’s what “Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott. Ein gute Wehr und waffen” and so on, but that was his book and this was in New Testament that I took with me and carried all the time. I’ll just show you how this was set up. This is where we had the communion wafers and we had a little bottle full of wine. Most of the time out in the field this would be sitting on my jeep, the hood of my jeep was completely flat and square in the front so I, I’m getting mixed up here trying to do it. I knew something wasn’t right. We put the flag just like this; just hold it there for a moment. I put a hymn book on each end just to hold it; this would be the way if this was my jeep. My assistant would be sitting on the bumper of the jeep here or on a five gallon gas can that we would take off the back of the jeep and he would be sitting on that pumping the field organ, you had to pump it. He was a pretty good singer, so we’d pass out the hymn books and he would lead in the singing and play the organ at the same time. I’m no singer. Virginia’s the musician in our family. These candles are pretty old; you could see the way they look. I tried to keep it shined up nicely, but this is the way I would put it up on my jeep. If we were in the basement of a house or in the living room of a house I would set it up the same way on the sink or the kitchen counter, wherever it might be and of course if we had a service in a civilian church and I was still going to have communion, I would set this up. I had my wafers in here and the wine and this was provided by the government. You didn’t have to buy that. They gave us $200 for our uniform and everything else. This was provided by the government. I think the stole was too, I’m not absolutely sure about that. This is the way it looked when I pulled up out in the field where the fellows were going to have a worship service. It might be Sunday morning; it might be Saturday night or Tuesday afternoon, whenever they could get together. If I knew the fighting was at a standstill for a while, we’d send word down through the commanding officer, the company runners and pass the word around that the chaplain was going to have a service at a certain place and a certain time. It didn’t necessarily have to be on a Sunday morning, but anytime during the day. I tried to keep it shined up, it doesn’t look too bad.

Looks new.

With my combat uniform on like that and with the helmet off I’d be standing alongside the jeep and my assistant would be sitting there on the other side on the five gallon gas can pumping the organ

Virginia: We saw him at least five, almost ten years ago. We met him in Jacksonville, Florida and saw him coming all the way over on the other side. I wouldn’t have missed him at all. He has passed away since then so I was glad we got to see him one more time.

He was a big Southern Baptist. That’s it.

Well thank you very much for sharing your memories with us. We really appreciate you doing this.