John F Misasi

Name: John F Misasi

Rank: T4

Date of Birth: February 24, 1922

Place of Birth: Illinois

War: WWII

Date of Service: 1941 – 1945

Branch: US Army

Unit: 742nd Light Tank Battalion

Locations: England, France, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Luxemburg, Germany

Prisoner of War: No

Interview Transcript

Today we’re with John F Misasi. John was born on Feb 24, 1922. He served in the United States Army, mainly in the European theater. The highest rank he achieved was as a T4. Today we’re in the Melrose Park Public Library and today is October 12, 2007. This is Fidencio Marbella and I’m an employee of the library. We’re also here with Heidi Krug, a Reference Librarian, also with the Melrose Park Public Library. This interview is being conducted for the Veteran’s History Project at the Library of Congress. Okay, let’s go ahead and get started John. Why don’t you tell me where you were when you found out about Pearl Harbor? What were you doing? Do you remember?

I was at home and listening to the radio and that’s where I heard about Pearl Harbor. And at that time I knew there was one fellow on the Arizona from Melrose Park. His name was Frank Yomine and we all felt bad for him. He was a very good football player at the Proviso High School and he had told his dad that he wanted to join and his dad said no. He was too young. He was seventeen and he kept pestering him until his father broke down and let him go. Little did he know that he was going to meet up with the sunken ship and his dad never felt right after that because he felt that he was responsible for his son passing away under that condition. He did what the son wanted him to do – let him go so he went.

So after you found out about Pearl Harbor, did you go and enlist right away? What was your reaction?

Well, being nineteen years old at that time I didn’t think much about joining the service or anything. I was an apprentice machinist and I was just starting to learn to make some money at fifty cents an hour as an apprentice.

That was probably good money back then.

Well, it was a start anyway.

So you went ahead and enlisted, where did you go to do that?

We had to go to Chicago. It was a bunch of us that went with a bus from Bellwood where they gave us coffee and rolls and from there we went to the center where they examined us first and then they classified you on when you wanted to leave, so I took a two week leave before I really went into the service. And we went to Rockford [Camp Grant], the center where they entered you into the service.

That’s where you were actually sworn in as soldiers? In Rockford?

Yeah.

Now, you left there for training camp, I imagine. Where did you go from Rockford?

From Rockford we took a train in Chicago and traveled five days to Seattle, WA [Fort Lewis]and we took our ninety-day training there. Three months of training.

What kind of training was this? Basic training?

Basic short order drills, marching, calisthenics of all different kinds. And from there we went down to Indio, CA where we were stationed in the desert area. Camp Laguna. However, when I got there they had a sign on the wall, “Who wants to go to school?” So I signed up and within two days I was at Fort Knox, KY.

So what kind of school was this that you signed up for?

Truck and tractor mechanic.

So they shipped you out from California to Kentucky?

Yeah, from California to Fort Knox, KY.

What was Fort Knox like?

It was very military oriented. When you went to school you had your books under your arm and you marched to the cadence of the army marching songs and you marched down the streets to the school with your books under your arm and everything was according to the army style and I felt proud to be one of the bunch that marched in the sequence to one another. And then when we went to school they had a teacher to teach you different parts of how to repair tracks on a tractor or a tank. We had heavy equipment like ten-ton wreckers that could lift a tank up. Showed us how to use that. I ended up being a truck and tractor mechanic and I also drove the ten-ton wrecker. Another fellow from Tennessee was my co-driver.

Did it take you a long time to learn to drive a ten-ton wrecker?

No, because I had some experience with a five-ton. But the ten-ton had many arms to extend from the truck and you laid on the ground and you could pick up a tank with. They had the, I forgot the nomenclature now, we had cables that mechanically pull the truck and you could pull and do many things with this cable. Say a tank fell over the side, we could hook it up under the tank and pull it upwards. We could put it back on its tracks so it could move again.

Now when you were in Ft Knox were you allowed to take leave at any time or on the weekends?

On weekends we were allowed to go home or wherever you wanted to go.

Did you usually come home on the weekends?

I usually did.

What did you do when you would come home on leave? What were some of the things that you tried to enjoy that you couldn’t in the army?

The family, because I was gone thirty-nine months and the few days that I came during that period was a break right off the start, but then I never came home after that.

So what was it like living in the barracks at Ft Knox? What was the food like?

Well, being young and always hungry whatever they gave you, you ate. Yeah, the food wasn’t bad.

Did you have a hard time adapting to military life?

No, I didn’t. I was always in favor of being in the army once I was in. I enjoyed my fellow members and I did the best I could. I was proud and when I went to school they gave me two stripes – T5. And they also gave me a certificate. I don’t think many people got a certificate.

What was the certificate for?

To show that I went to school and that I was graduated from a private to a T5.

So after you were done with Ft Knox, where did you head off to then?

From Ft Knox we went back to the desert area.

In California?

In California. It was called Camp Laguna [Indio, CA] which was in the Mojave Desert. That’s where we had the tanks, half-tracks and jeeps and it was very, very hot, like 120 degrees. And during the day you couldn’t work on any vehicles because it was so hot you couldn’t even touch them. They would allow us to go under a tank in the shade and cool off for a couple of hours until it got cooler and then we’d go out, maybe go out on some journey of driving through the desert. And if you were a driver you had a little porthole to look through [the M5 Tank].

The driver in the tank?

Yeah, the tank driver. Then you have others that are standing, a little higher than you and they could look up through the turret. If you’re the driver you could only look through the hole. There were many times that sometimes there was a rain-wash in the desert where it creates a dip and maybe you don’t see that and all of a sudden, boom, you go down and then you come back up again.

You actually learned how to drive tanks also?

Yeah, I was in a tank outfit for twelve or fifteen months.

What unit was that?

The 742nd Light Tank Battalion.

Do you know what kind of tanks they were?

It was an M5 howitzer tank. Had a short howitzer [barrel] where you could lob the missile.

So it wasn’t direct fire, more like a mortar?

It was more of a high lofted one. When it lands in the area.

Like artillery?

Yeah.

How did you like driving the tank?

Oh, it was a lot of fun, a lot of fun.

How long did it take you to learn to drive a machine like that?

It wasn’t very hard because all you needed to know was the two sticks you had. You pull the right one, you go right, you pull the left one you go left. Then if you pulled both of them, it’s the brake.

Very simple.

Yeah, it was simple. And they had two Cadillac engines on this tank and a hundred, two one hundred gallons of gas in two tanks, but they had one transmission. Two engines to one transmission for the power to go to [the sprockets to turn] the drive of the tracks.

One engine for each track?

No, they both went to the transmission and the transmission had the power of two engines because these tanks were pretty heavy.

Were they pretty fast?

These tanks were very fast. They’d go as fast as 60 MPH. And we also had rubber tracks on them, so you could go on a concrete highway if you wanted.

Did you?

No, we were out in the desert most of the time so we didn’t have to drive in the streets. The funny thing about the desert is the distance. You would think that five miles would be a long distance but out in the open like that it’d look like it was right next to you. We tried walking to a mountain one day and we thought we’d get there in one hour. We walked three hours and we didn’t even break the distance. It still looked far, so we realized that.

Gave up?

We gave up and came back. Then we had binoculars that are adjusted with some kind of a graph and you could measure. If you know the measurement of the item that is out there, like a half-track you can also figure out how many miles it is from your stance to the vehicle that you looked at.

After you were done with your tank training in California, where did you head off to then?

Our duty in California was to protect the coast from the Japanese at that time, and we also trained to go to Africa in the desert out there, however the Africa campaign was almost over so they sent us to Louisiana for swamp training with the tanks. There’s where we met a lot of mosquitoes and we learned how to use logs to pull out of a swamp and stuff like that.

Was this Fort Polk?

Camp Polk. At that time they called them camps, Camp Polk, Louisiana. Leesville. So we had our training there and while I was in training they transferred me to the field artillery. They were in need of truck and tractor mechanics. I and four others were transferred at one time.

How did you feel having to leave your original unit?

I felt bad because I was with the other unit for over a year and I felt like I was at home with them, but within a short time I got used to the new people I was with. We ended up in Camp Hood, Texas and from there we took a train to Camp Shanks, New York and we caught the ship there to go to England.

Now how long a trip was it going to England? How many days?

It took about thirteen days to get there.

What was that like?

Well, there was such an armada of ships that you couldn’t see the end of the ships, there were so many of them. However when we got to Liverpool, we were chased by a submarine, a German submarine and we were chased way up north, where it was very cold and we had to put on our heavy underwear and suits on. Then our anti-sub units finally chased him away and then we came back [to Liverpool].

Now what was it like having to spend thirteen days on a ship in the Atlantic? What did you do to pass the time?

There wasn’t much that you could do. There were hammocks to sleep on and sometimes we’d be up on top of the ship and most of the fellows were pretty sick, throwing up over the sides and there were about twenty or thirty toilets that had no seats or anything on and two bars to hold onto and they were using that in more than one way. But I was warned by some of the sailors that whatever you do, keep you stomach full. Eat! That’ll stop you from throwing up. So I did that.

Did that work for you?

Yeah.

So what was your reception like in Liverpool? Did you get to see a lot of the English people?

When we landed our captain had us all march like soldiers should march and said stand up straight and march like the soldiers you are. So we did. The people were very, very nice. So we made our march and they brought us to these Quonset huts and that’s where we stayed for a month while we got our equipment ready to go across the channel.

What did you have to do to get your equipment ready? What were the processes?

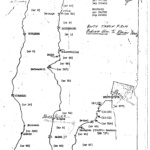

The guns were covered with Cosmoline. When you’re on salty water that could rust your equipment, so we had to clean all that stuff off and get it ready for battle. When we went to the English Channel we crossed it and went to the battle of Brest, the city of Brest and that was the submarine base the Germans had. From there they attacked the Atlantic.

Was this about June or July of 1944?

It was like July.

What were your thoughts when you left for France? Were you all nervous?

Well actually we didn’t know what was going on. All we knew was that we had to cross the channel. And we were field artillery so it wasn’t hand-to-hand combat. We were lucky in that part.

So you actually landed in Europe in Normandy?

Well that’s part of Normandy, on Utah Beach. They had two beaches, Omaha and Utah. Utah was to the south of Normandy and that was where the city of Brest was located.

So why was it important that the American Army had to capture Brest?

They had the submarine base there. We had to get rid of the subs because they were, they chased us away and it took us a good month with airpower dropping bombs and artillery dropping bombs. They had fortifications that were six feet thick, steel and concrete.

Were those the submarine pens?

That was the area where they were hiding, below ground and they had enough food to last five years, canned food, so they were well set to stay for a long time. But the tremors were so great that they couldn’t stand it anymore. So they gave up and our battle was over with that area. Then we kept moving up toward Paris and they had some small skirmishes on the way up there, like the town of Nancy and some others. By the time we got to Paris, it was already taken by the Americans. We marched down the Champs de Elysees through the Arc De Triumph and we felt like we were, like we had accomplished something. In a short time we headed for St. Vith, Belgium and at that time the weather was warm and the grounds were muddy and they couldn’t come towards us and we couldn’t come towards them, so we just stayed there for a while, until the Battle of the Bulge.

So this would have been sometime in the fall of 1944?

Yes. The Battle of the Bulge for us started for us, one morning in St. Vith. The German soldiers were dressed in white to match the snow. It got cold, bitter cold and they came down the slope and attacked our infantry and our infantry was annihilated. Our artillery guns were right behind them and they were ordered to destroy the guns with thermite bombs in the breech. So they destroyed all the guns and they radioed back to us to take off. So we put our equipment, all the gas tanks, cans on top of the truck and we went cross-country to the border of France. And we stayed there, well I stayed there for about three days and then I was ordered to take the captain to the front lines.

He needed a driver to bring him up there?

Yeah. And he needed someone who could understand a little German.

Is that why you were picked?

I had worked with Germans for a whole year and they spoke a lot of German and I knew a few words just by fraternizing with the people, so he took me with him. The snow was about this high.

About two to three feet?

Yeah, and we had chains on each wheel and it was four wheel drive, the jeep was, but no cover.

You had no canvas cover driving in the middle of winter?

It was very cold! Right, we had wool knit gloves which didn’t do very much good, and my fingertips caught a little frost. We stayed out in the frontlines for about thirteen days delivering messages from the back to headquarters. And then our clutch went out, couldn’t make a hill anymore. So we had to take the jeep in to have it repaired and after three days the captain says, well let’s go back. I told him captain, he was a friend of mine, I said I’m not a jeep driver, I’m a truck and tractor mechanic – I’d rather you take somebody else. So he did, he said okay.

He was good about that?

Yeah, he was a good guy. His name was Captain Howard Becker. He was of German descent, from New Jersey, very nice man. He was about, like thirty years old and we were like twenty-one.

More like a big brother?

Yeah, he was sort of balding already, but very smart and he often used to sit with me to put bearings on a wheel or something like that. He said, I never did that before, show me how you did it. So you get bearings and put some grease in the palm of your hand and press the grease through the bearing and then you put it on the vehicle. We used to do a lot of trucks for the Red Ball outfit, the ones that would deliver ammunition and stuff to the front lines. They were very rough with the vehicle so every once in a while they’d bring in ten or fifteen back to us. We’d repair them and then wait for another outfit that would take them back again. So we were always working, putting things together.

So the Red Ball, were they the supply trucks?

Yeah.

So would they drive from the ports to near where the front lines were? To bring supplies?

They would drive right to the fighting line, sure.

So that’s why the trucks got so much abuse?

Yeah, I guess they didn’t take their time driving either, in and out.

Just wanted to ask you, when you were driving around with Captain Becker, did you go to any headquarters buildings?

Yes.

What was that like, seeing the generals?

When I first went with him after the Battle of the Bulge started, we would take a whole building and there were generals and captains, all kinds of brass with maps on the wall and they’re figuring out what their next move was going to be. And that’s what we did for about thirteen days together.

Now while the brass were all talking about strategy and things, what did you do? Did you just kind of . . .

Well, I wasn’t too interested because I didn’t understand what they were saying anyway.

Did you end up going through the houses yourself and see what was there?

We would go into a house maybe at night time for cover, but not to investigate the house but we did sometimes take over like a lumberyard so we could use the stalls for repairing vehicles and there might be a woman with some children in there because all the men were not, they were gone, they were in service with the Germans. And we’d often give them some of our food, some flour, some sugar and they might make some cookies or something like that.

So you’d kind of trade.

We’d sort of protected them too, because there were many, even Americans that would come in there and try to steal blankets and pillows and stuff and we would stop them. You don’t belong here, you belong to another section, get out of here otherwise we’ll report you, and then they’d leave. So they were glad when we were there and they were afraid of the Russians because the Russians wouldn’t treat them that well.

Did you have a hard time communicating with them?

No, with the few words that I learned, I could converse and then we had one fellow from Austria, but American-born and he spoke a little German too.

So what happened after the Battle of the Bulge? How did we end up stopping the Germans?

Well, the reason why they got so far with their battle was the fog that was so thick, you couldn’t see in front of you and it lasted for three days. So our airpower was dead, they couldn’t go up in the sky so they [the Germans] made their push because they knew the layout of the land and they knew where the weak spots were and they came right through. When that happened, they gave me a bazooka to fire on a tank if it got close to you, knock out the track and then it would be disabled. However, when it did come toward me I couldn’t see who it was, whether it was American or German, so I had to let it go by. And I didn’t even see it, I just heard it.

Had you ever fired a bazooka before?

Oh yeah, we were trained for that. And a bazooka, when you fire it, it shoots out a flame so wherever you’re shooting it at, they’ll see where it came from – guess what they’re going to do. They’re going to knock out that flame.

You’re lucky you didn’t have to shoot it. So after the fog cleared, our air force was able to take to the skies again?

Our air force came and in a short time they bombed the strategic roadways and the Germans had to give up because they were outnumbered.

So this would bring us to about January, 1945?

It’s got to be around that time, yes.

So what happened, or what did you do after the Battle of the Bulge?

After the Battle of the Bulge, we had to go to Luxembourg and Czechoslovakia to halt the SS troops. They were needlessly killing civilians.

Was this in the concentration camps?

No, no this was in the city, Czechoslovakia, I have it on the map. But the people were very nice after it was over. The young ladies would come and put homemade medals on us to thank us for saving them from the SS troops. We were there for about two or three weeks and then we went down to Germany and we were assigned to the concentration camps [POW] for a couple of weeks.

Now what was that like? Which camps were you assigned to?

I don’t really remember the name, but they were young people, fourteen years old, fifteen years old and old people, like seventy or eighty.

In the camp?

In the camp. Because all the good soldiers were dispersed all over Europe.

Did you get to talk to any of them?

Oh yeah.

What were they like?

They weren’t afraid, I guess the war was over once they were in the concentration camp [POW] and they were not treated like Hitler treated them. Hitler treated the Jewish people like they were animals, the poor things, but these were all Germans themselves.

Were they relieved that the war was finally over?

Well, we only stayed there a few days to meet the people.

What was your reaction when the war in Europe was finally over? How did you find out?

Well, when we were in Czechoslovakia we found out it was over, so then we were anxious to get home. And you’re supposed to have seventy points or so to get out.

How did you earn points?

By the amount of time that you were there. So I had seventy two points and I was ready to leave, so we went to Marseilles, France, waiting for a boat to take us home and they went on strike, a longshoreman’s strike. From week to week, we were there three months!

Just waiting for a ship.

Waiting for a ship to take us home. So when we did get a ship, it was the Bardstown Victory ship, a small ship and we went through Portugal, and then from there we went through the Azores and there we had storms for three days. That ship was so small, it was always up in the air, with the propeller spinning in the air and that’s where a lot of people got sick.

How did you do?

I was okay, had a good stomach. It took us thirteen days to get home to see the Statue of Liberty.

What was that like when you first saw the Statue of Liberty?

Oh, that was really soul touching when you see that, and I had a camera on board and I took a picture of the statue as I came in.

So then after passing the Statue of Liberty, when you docked, was there a crowd there to welcome you back home? What was that like?

Actually, no. We were like . . .

You were old news by then?

Yeah, we were old news because it was three months after the end of the war, not three months, three weeks. The first ones that landed, I guess they were wined and dined and marched in the streets of New York. But we weren’t, and when we got in they fed us and then we got on another train to go home.

So you went from New York to Chicago?

Yeah, oh no we had to go to Rockford [IL] again.

So what happened in Rockford? That was your actual discharge?

That’s where we got mustered out.

How did you get home to Melrose Park from Rockford?

We took the train to Chicago, then I jumped on the elevated and we had a streetcar in Melrose at the time.

Down Lake Street?

It went all the way to 25th.

You took the streetcar home.

I had the duffle bag on my shoulder and we took it all the way to 25th and then I walked home.

Did your family know you were coming?

Yeah.

Was anybody there to meet you?

The house was full but nobody met me at the streetcar exit, they were all inside the house because we didn’t have any cell phones in those days.

Were they surprised when they actually saw you?

No, they knew I was coming but they didn’t know when.

So what was that like, your homecoming. The whole family was there?

Yeah, all my aunts and uncles and cousins, they were all there.

How long did the celebration go on? All day?

It was toward the evening when I arrived, so it wasn’t too long because many of them had to go to work the next day and in those days, I don’t know, unlike today they had to get up at six o’clock in the morning to get ready to go to work at seven.

Now did the town have any kind of homecoming for its soldiers? After they all came back?

I don’t remember of any but we did get certificates from the clerk and the mayor.

Did you have a difficult time adjusting when you came back from the war, when you first came back?

The only time they bothered me was the airport was so close, O’Hare Airport, a lot of planes went overhead and at night when I hear a plane it sort of, it did affect me for quite a while because we got bombed many times and you had to make a slit trench to get your body below the earth because when they dropped bombs shrapnel flies through and you’d find shrapnel on the side of your slit trench, the dirt that you would put on top of would catch the steel fragments.

So every time you stopped you had to dig a slit trench.

Well, most times if we were going to stop for any length of time. There were other times when we crossed the Rhine River and Mainz River you usually had to dig a hole into the sand, but the sand would always cave in. So this fellow from Tennessee, Raymond Sutton, he and I would go into the woods and try to find something more suitable and one time we found sod that was about twenty four inches thick and made a fort, a fort inside where it made one big room. So we would cover that up and we’d stay there during the night. Well during the night the Germans flared up the sky with light and all these poor guys that were in these holes, they all came out one at a time and came by us because we were hidden. There were about twenty of us in there. Luckily they didn’t shoot a bomb in there. We did survive that night and the next morning we took off again.

Did your unit ever have any casualties from the bombing?

We had casualties, but it was by mistake.

Friendly fire?

When you’re settling down at night, you don’t park underneath your truck to sleep. You make your slit trench first and that’s where you lay down and if it’s cold you use your sack, your sleeping bag. Use your sleeping bag, take off your shoes and you’d be in there for the evening. You’d go into the hole that you made, the slit trench so you’re protected in case of a sudden bombing attack. And being young, you don’t have the fear that you have when you get older. Really, you don’t have that fear, but today I would be!

Young and stupid.

That’s it, that’s why they want the young, they don’t realize the dangers involved.

Okay, well thank you very much for sharing your memories with us and we really appreciate your taking the time.

You’re welcome.